Items filtered by date: January 2019

Learning Styles in Coaching

The concept of learning styles generally refers to consistent differences in how individuals engage with learning content (Adey, Fairbrother, & William, 1999) and is widely used in education. People have different strengths, talents, work styles and interests and learning style and questionnaires can help us determine how a person processes information (Honey & Mumford, 1992). This in turn enables us as coaches to tailor our coaching session according to the individual’s requirement. Or so it should.

The literature points out a few problems with using learning styles. There is no standardised definition (Curry, 1983) of what a learning style is and questionnaires are highly subjective as they rely on the honesty of the client; there is no way to tell if they have answered truthfully or have simply responded in a favourable way. It’s considered a risk to use tools such as the Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) due to its questionable psychometric validity and reliability (Riding & Sadler-Smith, 1997).

Furthermore, there is a high risk of pigeon-holing (Adey et al., 1999), which can lead to a unilateral approach and incomplete supply of information. Our brains, styles and habits can change over the years and by identifying one person with one single learning style we, as coaches, might deny them the opportunity to expand their horizon and unintentionally limit them. The human brain is so complex that dividing the entire population into four compartments seems a bit inadequate to me.

Even knowing all this, I wonder if the whole concept of learning styles can be dismissed so easily, or if they could still be useful. Honeybourne (2006), a British education consultant, claims that the “recognition of a range of learning styles allows teachers and coaches to present […] skills in a way that best suits the needs of the learner.” The convenience and the simplicity of the learning styles concept cannot be denied, although the individual’s motivation plays a massive role in the learning process.

In summary, the idea of learning styles is splendid in theory. If used as a conversation starter it can be extremely useful, as long as we don’t put the client in a box without discussion or a more holistic enquiry of them as a person. Individuals are complex and there are many factors at play be they biological, socio-economic or psychological. It’s therefore most helpful in a coaching situation to present information in as many different and challenging ways as possible (Bailey & Schwartzberg, 2003). We want to stretch our clients but not bore or overstrain them. After all, our aspiration as coaches is surely that we won’t be needed after the coaching session(s). We need to equip clients with all means necessary for them to be able to help themselves in future

Adey, P., Fairbrother, R., & William, D. (1999). Learning Styles and Strategies: A Review of Research. London: King's College.

Bailey, D. M., & Schwartzberg, S. L. (2003). Ethical and legal dilemmas in occupational therapy (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Curry, L. (1983). An organization of learning styles theory and constructs (pp. 1–28). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (67th), Montreal, Quebec.

Honey, P., & Mumford, A. (1992). Learning styles questionnaire. Retrieved April 25, 2018, from https://resources.eln.io/honey-mumford-learner-types-1986-questionnaire-online/

Honeybourne, J. (2006). Acquiring skill in sport: An introduction. London: Routledge.

Riding, R. J., & Sadler-Smith, E. (1997). Cognitive Style and Learning Strategies: Some Implications for Training Design. International Journal of Training and Development, 1(3), 199–208.

Never Enough Time

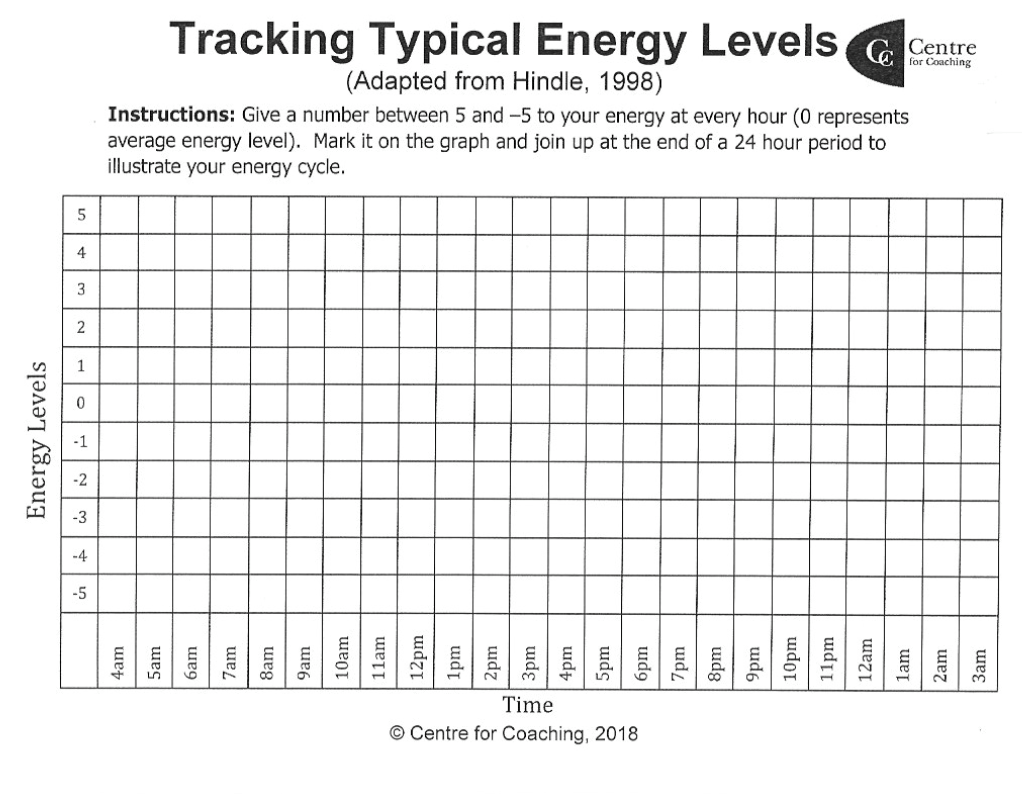

Even though many people plan and structure their time, few monitor their energy levels throughout the day, missing out on valuable feedback on the effectiveness of their chosen technique. A good coach will support individuals to make the best use of their time through logging not only time but also energy levels, helping them to transform, redirect, and fuel their energy capacity, improving performance, enhancing relationships and/or improving the quality of service they deliver (Loehr & Schwartz, 2001).

Research has emphasised a range of tools, including online and digital aids, such as smartphones or diaries, to monitor, assess and evaluate an individual’s natural energy levels and use of time. Using this information, areas of unused time and energy can be realigned, optimising performance and promoting a new context for personal and/or organisational change (Pammer, Bratic, Feyertag, & Faltin, 2015).

Anybody can use these techniques to move from managing time to managing energy. This can be particularly useful in a business setting, where traditionally downtime is viewed as wasted time and productivity (Santos, Wysk, & Torres, 2014). Combining time and energy tracking can highlight periods when staff may experience less energy and hence lower productivity, giving employers the opportunity to introduce new strategies including downtime and access to techniques such as relaxation and mindfulness, re-energising the workforce.

On an individual level, clients who claim that they ‘never have enough time’ are reacting to self-defeating thoughts that create a barrier to change and achieving their goals. Applying Cognitive-Behaviour-Coaching (CBC), the client can be suggested to have developed flawed cognitions, a fundamental belief that it is time that is the barrier to change, and which justifies their behaviours – of not engaging in the tasks needed to attain their goals (). CBC also highlights how thoughts can not only foster negative behaviours, but also sustain negative beliefs, leading the client to feel unmotivated, and that change is beyond their existing ability (Neenan, 2018).

Using time and energy logs can also offer a SMART method, drawing on GROW techniques (Renshaw & Alexander, 2005), enabling the client to be active in tracking their own time and energy. This aids autonomy and highlights where both time and energy changes can be drawn upon, facilitating a shift from the self-discipline rule to the ritual rule. In the ritual rule, time and energy logs offer feedback that helps individuals to develop downtime and rebalance energy levels, which can help them attain their goals.

Energy tracking can offer specific time-bound outcome measures, showing the impact of enabling downtime on reported energy levels and performance. In turn, such techniques can offer an effective programme for behavioural change to enhance not just individual performance but personal capacity for self-management and changes in self-beliefs. Coaching individuals in tracking their time and energy can help them to manage both more efficiently and intelligently, giving them the transformational power to change their lives and behaviours.

Loehr, J., & Schwartz, T. (2001). The making of a corporate athlete. Harvard Business Review, 79(1), 120–128.

Neenan, M. (2008). From Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) to Cognitive Behaviour Coaching (CBC). Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26(1), 3–15. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0073-2

Neenan, M. (2018). Cognitive behavioural coaching: Distinctive features (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Pammer, V., Bratic, M., Feyertag, S., & Faltin, N. (2015). The value of self-tracking and the added value of coaching in the case of improving time management. In Excellence in coaching: The industry guide (1st ed., pp. 467–472).

Renshaw, B., & Alexander, G. (2005). Super coaching. London: Random House Business.

Santos, J., Wysk, R. A., & Torres, J. M. (2014). Improving Production with Lean Thinking. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Living with Anxiety

We all have a story about why we do what we do.

Some might be in a profession because their career counsellor told them they’d be a good fit, or because they follow their parents footsteps or simply for monetary reasons, having bills to pay.

I started out as an engineer because a teacher told me I’m good with numbers and I choose the textile industry because of my parents family business. Then life happened and I needed to re-evaluate, needed to change and re-orient.

One incident changed everything once again and made me take the path I’m on now.

This is my story on why and how I became a psychologist and coach. It is personal, uncomfortable and overwhelming at times, but I can see the light at the end of the tunnel.

———

I should have known when they cancelled our flight and put us on the next one. We should have taken the sign, gone back home and had a long and generous breakfast. But we didn’t, and this flight became one of the most memorable ones of my life.

The start was uneventful and so was most of the cruising but just as the seatbelt signs came on to alert us to our imminent landing approach, the plane took a deep plunge. I later read that a plane doesn't drop more than three to five metres during turbulence, but my stomach in that moment would beg to differ. The whole cabin let out one simultaneous cry, which turned to a whimper and then silence.

Dead silence.

The plane plunged again, and shook left and right. I felt like a grain in a big bag of sand, or a boxer being soundly defeated – punched from all directions. I clutched my armrests, as if that would make a difference. I needed something to hold on to, something stable in a shaky metal tube thousands of feet above the ground.

I've read many times that people start to pray in such situations or that their life flashes by like a movie. My husband told me later that he was thinking of all the opportunities he’d missed and how much he still wanted to teach our children. My thoughts weren't that selfless though. In fact, they were quite the opposite. All I could think of was how much I abuse my body. Stuffing it with junk and poison. Yes, poison!

I made a deal then. With God, the universe, whoever was listening. "Let me land safely and I’ll never touch a cigarette again."

It went dark. Storm clouds amassed around us, immersing the cabin in a strange kind of twilight. It was not quite light and yet not fully dark. It engulfed us, teased us and breathed fear into some and bravery into others.

The mumbling got louder. Some were praying, I'm sure, some just nervously talking. I heard a cry here or there and a few swear words thrown in for good measure. People were falling back on their natural coping mechanisms I realised, and mine was calmness. Not the good kind, though. It was the stillness stemming from absolute terror. I was frightened like never before in my life. I wasn't even able to wipe away the tears running down my face or move my head to look around.

Plunge!

It wasn't over yet.

Shake left, shake right! My head hit the window. Then came an announcement. It was the captain telling us that he would try to land from a different angle. The engines roared and we gained height again.

There was a moment of stillness when we were out of the clouds but the relief I longed for didn't come. As the plane turned, my side lifted forcing me to look down to my left. My husband faced me, our eyes locked and our hands interlinked. No words were needed. He was as scared as I was and yet we were together. ‘Until death do...’ No, don't go there!

The shaking started again. Even heavier than before if that was even possible. I don't know how long it took for us to land. Five minutes? Ten? I started praying then, chanting the same phrase over and over again. I transported myself into a form of trance, still holding the armrest on one side and my husband’s hand on the other. I blanked out the noise and buried myself in a hidden place deep inside.

Touch down!

The force of the thrust slowing the plane brought me back to reality. We had made it. We had survived. But I still couldn't move. I still couldn't comprehend. We were safely on the ground and yet my throat felt as if a noose was tightly around it. I felt a squeeze of my hand and heard somebody talking to me, but I was frozen still.

It's then that I realised that my life had changed and would never be the same again.