Displaying items by tag: Energy levels

Never Enough Time

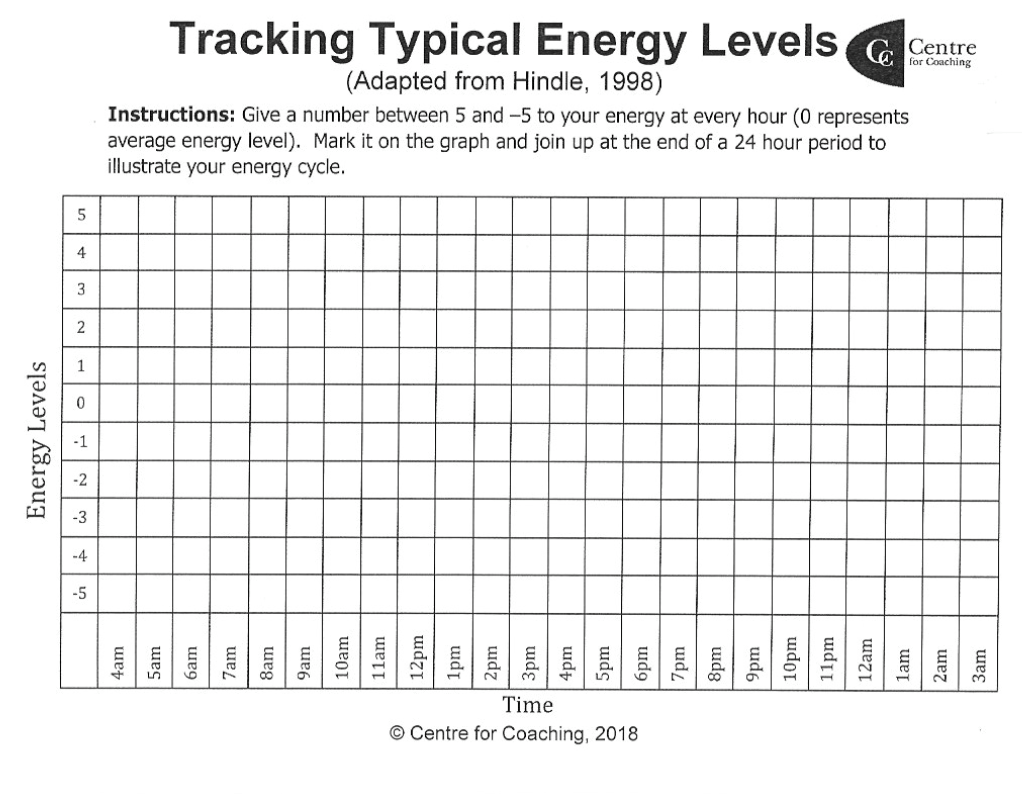

Even though many people plan and structure their time, few monitor their energy levels throughout the day, missing out on valuable feedback on the effectiveness of their chosen technique. A good coach will support individuals to make the best use of their time through logging not only time but also energy levels, helping them to transform, redirect, and fuel their energy capacity, improving performance, enhancing relationships and/or improving the quality of service they deliver (Loehr & Schwartz, 2001).

Research has emphasised a range of tools, including online and digital aids, such as smartphones or diaries, to monitor, assess and evaluate an individual’s natural energy levels and use of time. Using this information, areas of unused time and energy can be realigned, optimising performance and promoting a new context for personal and/or organisational change (Pammer, Bratic, Feyertag, & Faltin, 2015).

Anybody can use these techniques to move from managing time to managing energy. This can be particularly useful in a business setting, where traditionally downtime is viewed as wasted time and productivity (Santos, Wysk, & Torres, 2014). Combining time and energy tracking can highlight periods when staff may experience less energy and hence lower productivity, giving employers the opportunity to introduce new strategies including downtime and access to techniques such as relaxation and mindfulness, re-energising the workforce.

On an individual level, clients who claim that they ‘never have enough time’ are reacting to self-defeating thoughts that create a barrier to change and achieving their goals. Applying Cognitive-Behaviour-Coaching (CBC), the client can be suggested to have developed flawed cognitions, a fundamental belief that it is time that is the barrier to change, and which justifies their behaviours – of not engaging in the tasks needed to attain their goals (). CBC also highlights how thoughts can not only foster negative behaviours, but also sustain negative beliefs, leading the client to feel unmotivated, and that change is beyond their existing ability (Neenan, 2018).

Using time and energy logs can also offer a SMART method, drawing on GROW techniques (Renshaw & Alexander, 2005), enabling the client to be active in tracking their own time and energy. This aids autonomy and highlights where both time and energy changes can be drawn upon, facilitating a shift from the self-discipline rule to the ritual rule. In the ritual rule, time and energy logs offer feedback that helps individuals to develop downtime and rebalance energy levels, which can help them attain their goals.

Energy tracking can offer specific time-bound outcome measures, showing the impact of enabling downtime on reported energy levels and performance. In turn, such techniques can offer an effective programme for behavioural change to enhance not just individual performance but personal capacity for self-management and changes in self-beliefs. Coaching individuals in tracking their time and energy can help them to manage both more efficiently and intelligently, giving them the transformational power to change their lives and behaviours.

Loehr, J., & Schwartz, T. (2001). The making of a corporate athlete. Harvard Business Review, 79(1), 120–128.

Neenan, M. (2008). From Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) to Cognitive Behaviour Coaching (CBC). Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26(1), 3–15. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0073-2

Neenan, M. (2018). Cognitive behavioural coaching: Distinctive features (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Pammer, V., Bratic, M., Feyertag, S., & Faltin, N. (2015). The value of self-tracking and the added value of coaching in the case of improving time management. In Excellence in coaching: The industry guide (1st ed., pp. 467–472).

Renshaw, B., & Alexander, G. (2005). Super coaching. London: Random House Business.

Santos, J., Wysk, R. A., & Torres, J. M. (2014). Improving Production with Lean Thinking. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.